While computers work with bytes internally, many popular protocols like http or mail are text-based, requiring encodings that convert binary to text for transport, and later back into binary. There are four popular options for this task, which we will explore in this article.

What are byte encodings?

Many file formats and networking protocols need to transfer arbitrary binary data in a text-only context, for example to print bytes to a terminal for debugging, or upload an image file over HTTP.

In order to transfer bytes through text environments, they have to be converted (aka "encoded") to some kind of text-only representation, called a byte encoding.

These encodings typically work by first computing the decimal value for a byte or sequence of bytes, then mapping that number onto a position in a fixed alphabet of digits, letters and symbols. This process incurs a storage overhead depending on alphabet size, while larger alphabets suffer from decreased compatibility with text protocols.

The following size comparisons assume that encoded bytes are stored as ASCII, using 1 byte per character.

Base16 (aka "hex" or "hexadecimal")

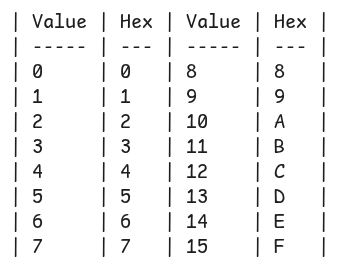

Arguably the easiest and one of the oldest byte encodings is hexadecimal, using only 16 characters:

Two characters are used to store a single byte value, resulting in 100% storage overhead (storage size doubles compared to raw byte size).

While the least space efficient, hex is also the most compatible and accessible option, since most formatted printing functions in programming languages support printing arbitrary bytes as hex directly using the %x formatter and the lack of symbols in the alphabet makes it perfectly safe for use in urls, filenames and text-based protocols.

It is also the easiest to convert back into decimal values for humans, and remains sortable, producing the same order that sorting the raw bytes would have produced. Additionally, its alphabet choice allows it to remain case insensitive, since turning the entire hex string into lowercase allows it to be decoded, no matter the previous letter capitalization,

It is used in scenarios where simplicity for humans matters, like debugging output in terminals or text based log files, for example network- or memory dumps.

Hex is also preferred in situations where compatibility is more important than size, such as string representations of hashes and UUIDs.

Base32

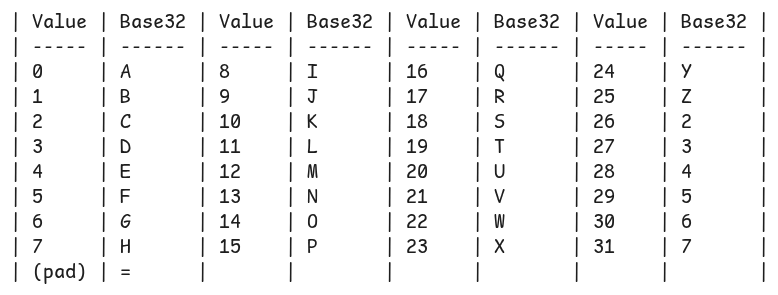

This encoding uses an alphabet of 32 characters, plus an additional one for padding incomplete values:

Eight characters store 5 bytes, causing a 60% storage size overhead. Since one character represents 5 bits in this scenario, base32 requires the use of the = sign as a "padding" value when input byte count is not neatly divisible by 5.

While less popular, base32 does fill a niche use case rather well: When you need to encode bytes and ensure full compatibility with text-based protocols and file formats (aka no special characters), which may need to be read/typed by humans, but without the need for the sortable features or humans converting the text back into decimals in their head.

The alphabet decision to omit digits 0 and 1 further improves this benefit, as it removes ambiguity with letters (lowercase L and 1, uppercase O and 0). It also retains the same case insensitivity properties as hex.

A frequent scenario is encoding numbers for urls, like url shorteners or link generators (image upload pages, pastebins etc). These urls may need to be typed by humans when sending across text channels or devices, but they do not need to decode them manually (or at all, really).

Base64

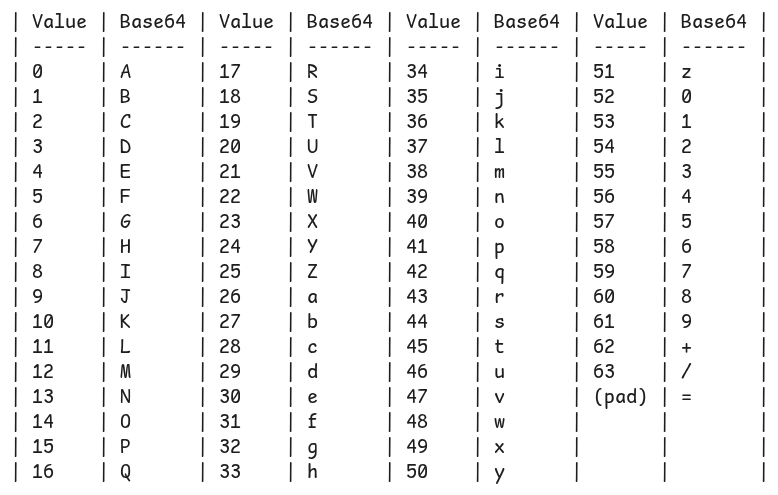

As you might expect, base64 uses 64 characters in its alphabet, as well as a padding character:

Four characters store 3 bytes, resulting in roughly 33% storage size overhead. One character encoding 6 bits means the = character is needed as padding for input byte counts not divisible by 3.

Base64 is, together with hex, the most popular byte encoding in use today. It strikes a balance between output size and compatibility, although the use of characters like =, / and + breaks compatibility with some url contexts (though there are less common url-safe variations) and text protocols, but remains usable enough for most use cases. It is also case sensitive.

It is used to encode openssh private and public keys, arbitrary file contents in data urls (e.g. when inlining images into html documents), or to transfer mail attachments.

For use cases needing to deal with files or larger byte sequences, base64 is often the perceived sweet spot between size and compatibility.

Base85

Arguably the largest popular byte encoding is base85, using most of the printable ASCII range while avoiding some specific whitespace and control characters. Since the selection of characters to avoid varies per protocol and format, there are multiple alphabets for it, tailored for their use case. Notable versions used are

ascii85 or "adobe base85", mostly used in pdfs and postscript

z85 aka "zeromq base85", mostly used within the zeromq library

git base85, used for git binary deltas and patches internally

Base85 can encode 4 bytes into 5 characters, yielding only 20% storage overhead. Values not divisible by 4 may require padding, although padding implementations can vary by alphabet.

It is mainly useful in situations that benefit from smaller storage sizes while needing to avoid only a few control characters; it is case sensitive and not safe for use in urls or filenames.

There are theoretically other encodings like base91/95/122, but they have little to no room to avoid select control characters and their storage space improvements are marginal, so they are rarely ever used in the real world